The Impact of Physical Health on Mental Health

Counsellors Perceptions

By Caroline Barrett

January 2019

I hear and read terms such as holistic, biopsychosocial and working with the ‘whole person’ a lot in relation to Counselling practice (Casado Kehoe & Kehoe, 2008; Cooper, 2008) and I speak to Counsellors who identify with these ideas, particularly in relation to self-care. Anecdotally I cannot think of one Counsellor I have spoken to who doesn’t use some aspect of physical care to support their mental health, whether that’s spending time in nature, exercising or in food choices. However, when it comes to acknowledging the impact of physical health on the mental health of our clients, things seem to get a bit woolly. This is reflected within the BACP (Bond, 2016) ethical framework which clearly defines physical and psychological health of therapists as necessary, but when it comes to our clients we commit to promoting their ‘wellbeing,’ a term which is notably vague in comparison.

As Counsellors we also lack a clear model within which to frame physical health concepts, Maslow’s hierarchy of needs (Lester et al, 1983) highlight physical health as a necessity but do not provide any further framework on how practitioners might actually integrate or address these concepts within client work. Although there is some indication that models of care arising from resilience research may begin to fill this gap (Bolton et al, 2016; Terte et al, 2009), these are far from mainstream within counselling theory. This is important as it links to another key point in the ethical framework that practitioners are bound to work within their competencey (Bond, 2016), so if counsellors are not using a theoretical model are they avoiding this subject with their clients entirely? Are they using research? Personal experience? Are they aware of the impact of physical health on mental health at all or is their knowledge framed within more traditional concepts of mind/body divide from which psychological theory has grown?

This led me to research Counsellor concepts of physical wellbeing research and its place in therapeutic practice.

During the course of my initial research it became clear that nationally and internationally guidelines and policy have a strong drive towards health promotion, support of physical health as part of improved mental health (National Institute for Health & Care Excellence, 2013) and health modifications as part of necessary strategy to manage the complexities of mental health conditions (Sarris et al, 2014; Jacka & Berk, 2012). In contrast academic literature directly relating to Counsellor’s perceptions of physical health and its impact on mental health holds virtually no clues, although some inferences can be made from other professions these mostly focused on barriers to practitioner’s support of lifestyle modifications.

In my research 72% of counsellors who responded to a simple questionnaire indicate that they are aware of current research relating to the impact of physical wellbeing on mental health (including areas such as sleep, diet, exercise, exposure to green spaces and sunlight) and that they did incorporate this knowledge into their practice.

Two focus groups were then conducted, the aim of which was to find some nuance and depth in relation to the research question. These focus groups were recorded, transcribed and then their content analysed for themes.

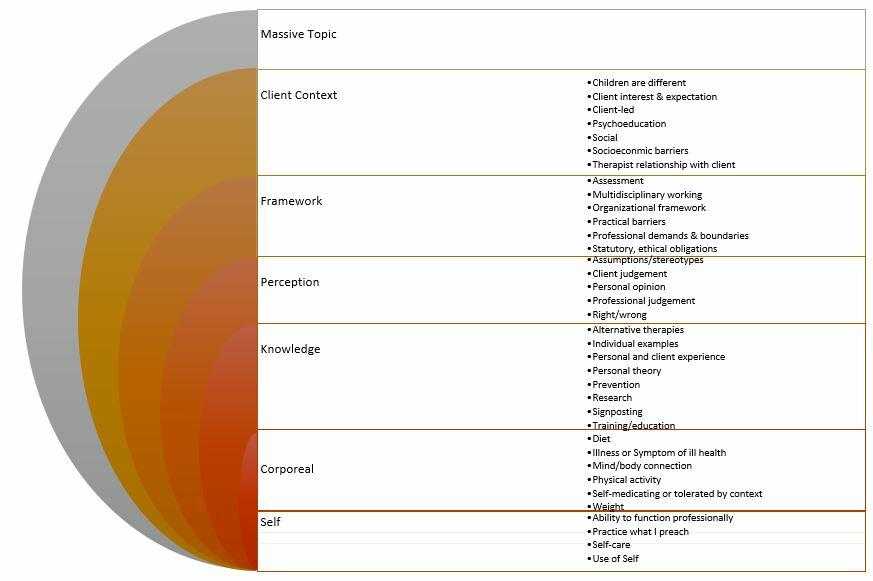

The resulting analysis indicated what a massively complex concept the impact of physical health on mental health and Counsellor’s perceptions are. It is also notable that many themes are intrinsically linked, for example ‘personal opinion’ was linked with ‘personal experience’ both for self and individual examples from clients. I have included a breakdown of the themes in the image below.

The underlying aspect of Counsellors perceptions was a sense of individuality which fits within accepted ideas around client-led practice but also within ideas of use of self within the context of therapy (Lawson et al, 2007). Whilst initially these may appear at odds, in the context of theories about relationship as the crux of therapy (Horvath, 2004) this is logical.

This research also highlighted how sensitive to judgement therapists appear to be both for their clients and by them, as well as wider society. This makes the topic of physical wellbeing more contentious when approached from a professional standpoint as it appears by it’s nature to be incredibly personal and as such likely controversial.

Personally, this leaves me with many more questions than answers, such as: do we have a duty of care to our client’s which includes acknowledging their physical health? Does the BACP need to clarify it’s position in relation to wellbeing? What constitutes adequate or appropriate research on which to base our practice? Do we need a coherent professional identity to ensure we are part of research and multidisciplinary discourse? Can we have both a consistent professional identity and or evidence-based practice and not lose the relational, individualistic care that makes up the heart of effective therapy?

This research is subject to a variety of limitations, but in the absence of any other literature directly relating to counsellor’s perceptions it does provide a glimmer of insight, as well as indicating potentially rich avenues for further enquiry.

About the Author

Caroline's work as a Doula and an interest in supporting people through life transitions led her to complete the Foundation degree in Integrative Counselling at Iron Mill College.

She went on to develop her engagement with research, gaining a BSc in Counselling and a MSc at Bristol University in the Psychology of Education whilst maintaining a keen focus on how this can be practically applied to support Client's wellbeing within her own research studies.

Caroline has previously worked within NHS settings and is currently in private practice in Exeter and Online, with a focus on clients seeking change and those experiencing anxiety and depression. Her position as Co-Chair of Taunton Association of Psychotherapists enables her to engage with a broad range of Speakers and fellow professionals in the area of Counselling and Psychotherapy as part of her desire to engage in ongoing learning.

References

Bolton, K.W. Praetorius, R.T. & Smith-Osborne, A. (2016) ‘Resilience protective factors in an older adult population: a qualitative interpretive meta-synthesis.’ Social Work Research. 40(3)pp.171-182.

Bond, T., (2016) Ethical framework for the counselling professions. Lutterworth, Leicestershire. British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy.

Casado Kehoe, M. & Kehoe, M.P. (2008) ‘Using genograms creatively to promote healthy lifestyles.’ Journal of Creativity in mental. 2(4)pp.19-29. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1300/J456v02n04_03 [Accessed: 24/10/2017]

Cooper, M. (2008) Essential research findings in counselling and psychotherapy: the facts are friendly. London. Sage Publications Inc.

Horvath, A.O. (2004) ‘The therapeutic relationship: Research and theory. An introduction to the special issue.’ Psychotherapy Research. 15 pp.3-7.

Jacka, F. & Berk, M. (2012) ‘Depression, diet & exercise.’ The Medical Journal of Australia Open. 1(4)pp.21-23.

Lawson, G. Venart, E. Hazler, R.J. & Kottler, J.A. (2007) ‘Toward a culture of counsellor wellness.’ Journal of Humanistic Counselling, Education & Development. 46pp.5-19.

Lester, D. Hvezda, J. Sullivan, S. & Plourde, R. (1983) ‘Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and psychological health.’ The Journal of General Psychology. 109pp.83-85.

NICE (2013) Into practice guide. London. National Institute for Health & Care Excellence. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg30/chapter/introduction-and-background [Accessed: 22/11/2017]

Sarris, J. O’Neil, A. Coulson, C. Schweitzer, I. & Berk, M. (2010) ‘Lifestyle medicine for depression.’ BMC Psychiatry. 14(107)pp.1-13.

Terte, I.D. Becker, J.& Stephens, C. (2009) ‘An integrated model for understanding and developing resilience in the face of adverse events.’ Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology. 3(1)pp.20-26.