My Voice Matters

By Heather Jenkin

Every child’s voice matters, but for some children there are various hurdles to overcome in finding their voice. Research tells us that 1 in 10 people experience difficulties with understanding and describing their own emotions (Salminen et al, 1999). Children who have experienced developmental trauma, post traumatic stress disorder, and some of those who are neurodivergent, are examples of children who can experience this obstacle (Krystal, 1979; Zeitlin et al., 1993).

‘Just because I struggle to put how I feel into words it doesn’t mean I don't feel things. In fact, the worse I feel, the more I struggle and often default to, “I'm fine”.’ www.autistica.org.uk.

This obstacle has been defined as alexithymia. Peter Sifneos first described alexithymia in the early 1970s. The word comes from Greek: ‘a’ meaning lack, ‘lexis’ meaning word, and ‘thymos’ meaning emotion — i.e. having a lack of words for emotions.

During the 20 years that I have worked therapeutically with children, I have noticed that most of those children had difficulties not only with putting their feelings into words, but also with not understanding what they feel. As such, I have adapted my therapeutic practice to help scaffold children’s language skills to try and help them find their voice.

Neuroscientists have discovered that developmental trauma and some neurodivergence can affect the area of the brain that controls cognitive thoughts, language skills and executive functioning (Perry, 2021) and (Barkley,2018). This could go some way towards explaining how alexithymia originates. One way to bypass this part of the brain is to work with the child’s limbic and sensory system to help them access their feelings from the emotional part of their brain. As a trained play and creative arts therapist, I have seen many children find their voice using limbic based therapies using the creative arts; drawing, painting, sand tray, clay therapy are just a few approaches that can help a child connect with the feelings in their body. Margot Sunderland sums this up beautifully:

‘Everyday language is a language of thinking, whereas speaking through a story, or playing out what you want to say with clay, sand tray, art, means you are using the language of imagining. This is the child’s natural language.’ (Sunderland, 2001)

I have tried all sorts of different language-based tools to help the children and young people find their voice and after lots of attempts, my inclination is to keep it simple. One of the most successful methods I have found is to use the zones of regulation.

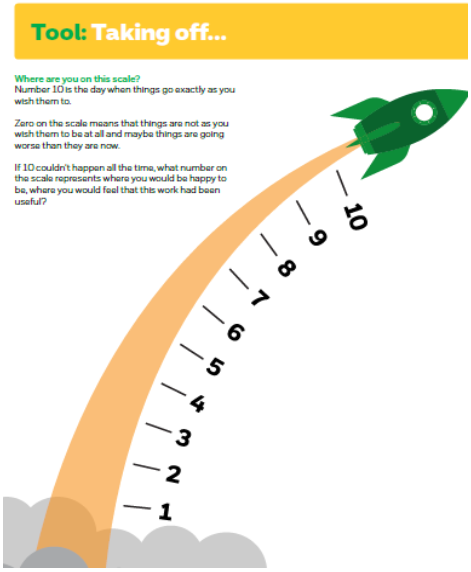

I have found the specific colours linked to emotions mapped in the zones of regulations helpful when working with children (www.zonesofregulation.com). Please see Figure 1; quite often a child will reply with ‘I feel yellow’ today as opposed to feeling worried, for example. We can then try and break down the feelings to help them be more specific by using solution focussed techniques such as scaling; see Figure 2. for an example of this. For instance, we can ask questions such as, ‘How

much yellow do you feel out of 10’? What colour were you at break time? Incorporating these simple techniques can sometimes help a child find their voice to then be able to process what their voice is telling them.

.png?1707214618107)

Figure 1

Figure 2. NSPCC Solution focussed toolkit

I firmly believe that every child and young person’s voice matters, however, I also believe as practitioners we can help a child find their authentic voice by considering whether their language skills need scaffolding or a creative approach can help them access their voice.

There are a few remaining places available on the Working Therapeutically with Neurodivergent Children Course running this Saturday, 10 February at our Poole campus.

CLICK HERE to book your place, while they are still available.

References www.autistica.org.uk.

www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326451

‘Neuroscience and the magic of play therapy’ Article in International Journal of Play Therapy · January 2016

Perry, B and Winfrey, 2021, What happened to you? Bluebird, USA

Barkley, Russell (2018). Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment, Guilford Press.

Salminen JK, Saarijärvi S, Aärelä E, Toikka T, Kauhanen J. ‘Prevalence of alexithymia and its association with sociodemographic variables in the general population of Finland’. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 1999 Jan;46(1):75-82.

Sunderland, M (2001) Using Storytelling as a Therapeutic Tool with Children, Taylor and Francis Ltd

NSPCC (2015). The Solution Focused Practice Toolkit. Available at: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/research-resources/2015/solution-focused-practice-toolkit

www.zonesofregulation.com